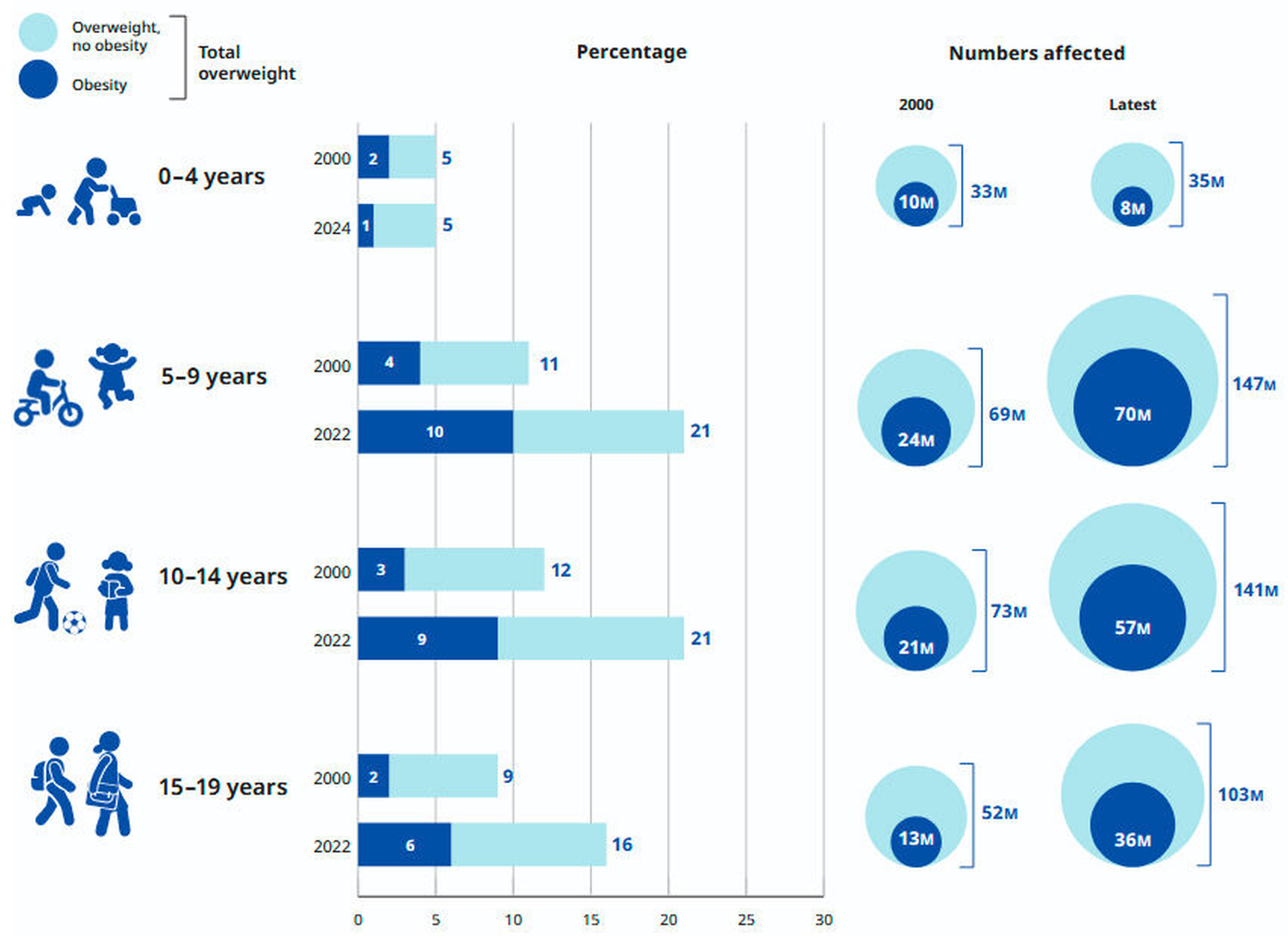

Weltweit mehr Kinder und Jugendliche adipös als untergewichtig

Jeder Fünfte im Alter von fünf bis 19 Jahren (391 Millionen Menschen) ist laut einem neuen UNICEF-Bericht übergewichtig – jeder Zehnte (188 Millionen) sogar adipös. Damit löst starkes Übergewicht erstmals Untergewicht als die häufigste Form der Fehlernährung bei Kindern und Jugendlichen ab. UNICEF warnt deshalb vor dem erhöhten Risiko für lebensbedrohliche Krankheiten. Die Organisation sieht als Hauptursache die ständige Verfügbarkeit und Vermarktung von ungesunden Lebensmitteln im analogen und digitalen Umfeld der Kinder.

Der Bericht hebt positive Maßnahmen hervor, die Regierungen ergriffen haben. In Mexiko beispielsweise – einem Land, in dem Kinder und Jugendliche häufig übergewichtig sind und zuckerhaltige Getränke und stark verarbeitete Lebensmittel 40 Prozent der täglichen Kalorienaufnahme von Kindern ausmachen – hat die Regierung kürzlich den Verkauf und Vertrieb von stark verarbeiteten Lebensmitteln und Produkten mit hohem Salz-, Zucker- und Fettgehalt in öffentlichen Schulen verboten. Davon profitieren mehr als 34 Millionen Kinder, so die Hilfsorganisation.

Der UNICEF Child Nutrition Report 2025 stützt sich auf Daten aus mehr als 190 Ländern und umfasst Haushaltsbefragungen, modellierte Schätzungen, Prognosen und Umfragen. Die Kategorien Übergewicht, Adipositas und Untergewicht wurden anhand des Body-Mass-Index (BMI) definiert. Für Kinder im schulpflichtigen Alter und Jugendliche im Alter von 5 bis 19 Jahren gilt:

Übergewicht ist als ein BMI definiert, der mehr als eine Standardabweichung über dem Median liegt.

Adipositas ist als ein BMI definiert, der mehr als zwei Standardabweichungen über dem Median liegt.

Untergewicht ist als ein BMI definiert, der weniger als zwei Standardabweichungen unter dem Median liegt.

Fehlernährung bei Kindern hat drei Dimensionen: Unterernährung (Wachstumsverzögerung und Auszehrung), Übergewicht/Adipositas und versteckter Hunger oder Mikronährstoffmangel.

![On 21 August 2023 in Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia, G'okie Samuel, 14, poses for a portrait in a grocery store he frequents in downtown Kolonia. The shop sells mostly imported goods from the western Pacific.

The Micronesian island of Pohnpei is home to more than 30,000 people. Despite being surrounded by rich waters and lush greenery, the island's food environment has become saturated with processed imports from both sides of the Pacific Ocean, sidelining traditional root crops and sea produce.

For lunch at Pohnpei Island Central School, students can choose between healthier offerings such as dishes with rice and meat, sandwiches and fruit, or less nutritious options like instant noodles, sugary snacks and drinks.

G’okie says, “At my school, we have a place where we buy our food and drinks. My family has told me not to buy crackers and soda because it’s not good for my body.”

Gloria, the school’s shop owner, states, “My bestseller is my brownies. What I noticed is the students like the processed food versus our local healthy goods. I think that we are so programmed in just going to a store and it's fast and easy and tastes good. Not thinking about if it's really good for you.”

Cromwell Bacareza, Chief of the UNICEF office in Micronesia, describes the issue of overweight and obesity in the country: “In Micronesia, more than 50% of children and adolescents are [living with] obesity. A lot of children now are consuming more processed food, and what's available and more convenient are those processed foods that they can actually buy immediately. Rather than going to healthy snacks or vegetables and fruits, there is an increasing demand for ramen, candies and soda. The schools contribute significantly, especially when children, what they eat and what they learn in schools, they bring that habit or that learning to the community. If what they learn in school is eating sugary food or sugary drinks, then we are facing a danger of having a vicious cycle. A school has to be a healthy environment for children to be able to thrive.”

UNICEF is advocating for a school policy that only allows healthy food to be sold in schools, and many schools are working hard to keep their canteens free of ultra-processed foods.

G’okie typically eats healthier foods at home than he does at school. He says, “What I tend to have in the evenings is rice and fish. We also add breadfruit to the basket. I believe the reason why I eat fruits and vegetables is because it's good for your body and it will keep you healthy.” G’okie also likes the thrill of climbing trees near his house to pick fruit.

Cromwell notes, “In Micronesia, there is an abundance of fruits and vegetables: papaya, pineapple, guyabano, avocado. We need to advocate more for people to make use of this. They can continue eating ramen but they can also infuse some vegetables in there that is available locally.”

Leilani, G’okie’s grandmother, thinks back on how much simpler nutrition was when most of the options were locally grown – often self-grown – staples, before advertising took hold and influenced young minds making decisions about which foods to consume. “Before, no chocolate, no branding, nothing. Only local. We raise and grow, we eat.”](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/f/csm_589335-flexible-1900_9af3858de2.jpg)